Hometown pride in the Hall of Fame: Tyler County native Jessie White proves every step can be a teachable moment

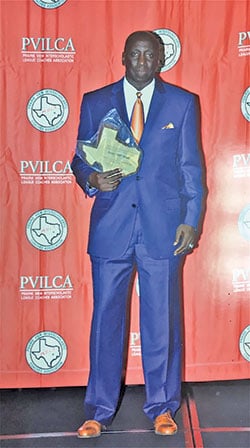

Jessie White at the Prairie View Interscholastic League Coaches’ Hall of Fame induction ceremony last week.By Chris Edwards

Jessie White at the Prairie View Interscholastic League Coaches’ Hall of Fame induction ceremony last week.By Chris Edwards

Soft-spoken and insightful, Tyler County native Jessie White is the type of man who exudes kindness and intellectual depth.

“It can happen,” he said. With one simple three-word sentence, White referred to the limitless capacity all humans possess to achieve things toward their betterment. “I’ve never allowed barriers to stop me,” he said.

White, who was just named to the Prairie View Interscholastic League Coaches’ Association Hall of Fame “hasn’t changed in 64 years,” according to his wife, Wanda, but beneath his calm, gentle demeanor is one of the greatest coaching minds the southeast Texas region has known. White tends to eschew labels such as “legend,” though, and said it even sometimes angers him when people refer to him in such ways.

White, who grew up in Warren, has worked for 40 years at West Brook ISD, where he led the Lady Bruins to more than 350 wins throughout the course of his career.

He is now retired from coaching, but is still teaching, and for White, life is chock-full of teachable moments. White, who teaches history classes at West Brook High, tells his students that he has lived through much of what he lectures about. He came of age during the age of segregation and was among the first high school class of Black students to go through Warren High School for all four years of high school, after the district had integrated.

For White’s induction in the PVILCA Hall of Fame, he was brought in under the category of “Bridging the Gap,” which represents the integration of the two sports and academic competition leagues, the Prairie View Interscholastic League and the University Interscholastic League.

The PVIL represented Black high schools from 1920-70, and the association has worked hard to preserve that history and honor individuals who fought adversity and achieved great things. Much of the history of those Black schools has disappeared with the passage of time, and White said the organization has dedicated itself to preserving that history.

White shared the “Bridging the Gap” induction honors with 10 others. White said he was “really excited” when he received the news of his induction. “It was insane…and caught me off-guard,” he said. Wanda called the recognition “well-deserved.”

In his acceptance speech, which took place at the ceremony, held in Houston at the Marriott South hotel, White did not run down memory lane to recall his past achievements on the basketball court, but spoke to something “bigger than basketball” – the fulfillment of dreams and acknowledging those who have supported him in his journey, including his family, friends and fraternity brothers.

It was an honor that, heretofore, White said he could only envision in his dreams. White is quick to point out that he is a proud product of Tyler County. “I’m very proud of growing up in Tyler County,” he said.

He returns to visit relatives as often as he can and said that for a lot of his collegiate career and during his coaching years, he could not find the time to return home, but looks back with fondness on the place where he came of age. “I carry Tyler County with me wherever I go,” he added.

When he graduated from Warren High School in 1976, White was not only a top-notch multi-sport athlete, but a top scholar. He said that he knew from an early age that despite his athletic abilities, he needed to place his chief emphasis on his books. In fact, when he was being scouted to play collegiate basketball, he was still recovering from a knee injury he sustained during his senior year, and doubted he would make it, but he did.

The injury sidetracked everything, he said, but in spite of it, he received a basketball scholarship to Temple Junior College before transferring to Sam Houston State University, where he would earn his bachelor’s degree with a double-major in sociology and history and a minor in kinesiology. Later on, he earned his master’s degree from Prairie View A&M in educational administration.

In his preparation to become a coach, White learned about coaching sports by working alongside people like the late Alex Durley, Cynthia Doyle Perkins and Dr. Charles Breithaupt, who is currently the Executive Director for UIL.

White said he views athletes as doing a job, and does not feel the need to cheer on someone for scoring a touchdown or sinking a basket.

White said that the integration process was sometimes difficult. He spent his elementary school years at Red Oak Elementary before transferring to Warren ISD when the schools became integrated in 1965-66. Prior to that, Black students went to high school at the Henry T. Scott High School in Woodville, as there was no campus for Black students in Warren.

White said that despite growing up in poverty as part of a large family, he still felt the support of the community, however, it was sometimes on the road as an athlete where he encountered bigotry in his high school days.

He said there was name-calling in some locales, and some coaches even warned Warren coaches not to bring Black athletes onto their campuses.

White said that seeing the extremes of the days of the segregated south to integration and his days as a star athlete could sometimes demonstrate odd scenarios.

He told a story of accidentally going into a gas station restroom as a little boy with a “Whites Only” sign upon the door, which he mistook for his surname, to mean that only he and his family could use the restroom. The gas station proprietor did not look favorably at this action and yelled at young Jessie. Years later, when he was a basketball standout for the Warriors, that same man invited him to his home for dinner.

White said he doubts the man had any idea that he was the same young boy who used the “wrong” restroom, or even remembered the incident, and he did not remind him of it, either.

The sport of basketball took White all over the world, and although he had great success on the court “it wasn’t everything to me,” he said.

Still, as fierce of a competitor as White is, and has been throughout his life, he still has regrets. He turned one of them into a teachable moment to help encourage his athletes. He said that due to a personal matter between a coach and himself, he quit playing the sport that fueled his legend his junior season as a Bearkat. “I tell kids now to not give up on your dream,” he said. “I wish I would have never done that…quitting is forever.”

White’s induction brought praise from some of his former players, many of whom consider him more than a coach, but a mentor.

His record for the district he has called home for 40 years speaks volumes of a man who is esteemed in the highest by his generations of students and his colleagues. Aside from his record-breaking tenure of coaching girls’ basketball for the Lady Bruins, White has also coached everything from track and field to volleyball, and he helped lead West Brook’s football team to a state championship as an assistant coach. He accomplished the same feat with the school’s track team. White also was recognized by the Texas Association of Basketball Coaches as well as the Texas Girls Coaching Association for his contributions to Texas high school sports.

“Leadership is about making others better as a result of your presence and making sure that impact lasts in your absence,” said Shaquita Brady, who added the honor was “well-deserved.”

Arie Wilson, who graduated West Brook in 2000, said “Thank you for making such an impact on not only the game, but in my personal life.”

Another former player and student, Liz Landry, who spoke about her mentor quoted him: “It’s what you do when no one’s watching that counts the most.”

White’s influence outside the classroom is evident in his former students, according to Wanda, who said that West Brook alumni who played under White and wind up at the same colleges and universities are recognizable to one another in the way they conduct themselves. She said the students who pick up after themselves and strive to keep their grades up are identifiable products of Coach White’s lessons on and off the court, even if they don’t know one another.

Former student-athlete Katlyn Ferguson Clark said that White expected a “Class-Act from young women,” and said “Thank you for setting the bar so high. I’ve always carried that standard with me and think of [Coach White] often.”

As far as his teaching and coaching philosophy goes, White said he would tell other educators “you do you.” “When I started developing my own way of doing things is when people really started to respect me,” he said. “You also must respect the people you are working with, as well as those you are working against and the officials, as a coach,” he said.

The calm and cool gentleman does not seem like the type to do so, but he admits that at one time he could pull off chair-throwing fits, ala Bobby Knight, but he found that it was not the way for him, nor did it garner respect.

“We’re all still learning lessons. I’m still learning lessons,” he said.